Imagining single-member constituency elections in South Africa

Please note that I write here in my personal capacity. The views expressed here are not those of my employer.

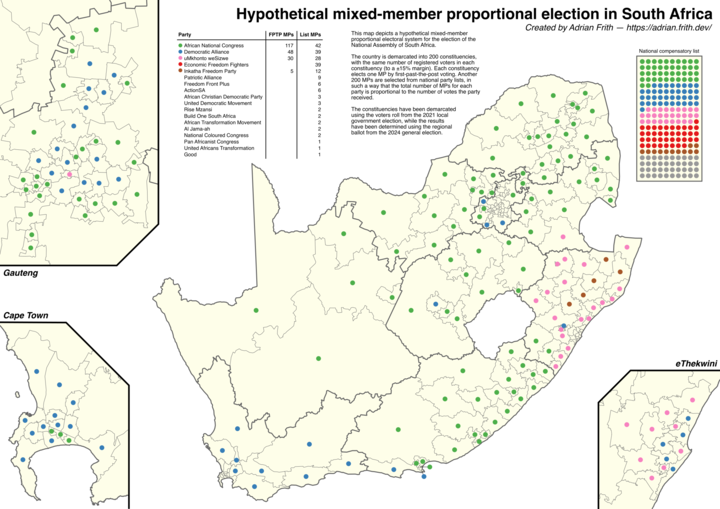

The 2024 election is behind us, but there is still discussion about electoral reform following the introduction of independent candidates and the separate regional ballot. Consequently I thought it would be interesting to update my imagined demarcation of single-member constituencies for 2024.

I envisage such a demarcation as forming part of an overall mixed-member proportional (MMP) electoral system. In such a system, the 200 members of the National Assembly who are currently elected by proportional representation based on each province’s regional ballot, would instead be elected by first-past-the-post (FPTP) voting in 200 constituencies. The other 200 members elected from the national compensatory party lists would remain, so that the overall composition of the National Assembly would still be proportional.

Below is the result of that process as an image. I have also created an interactive map where you can explore in more detail. Tapping on a constituency on that map will show the name I gave it and its election results based on the 2024 regional ballot.

Demarcation process

I demarcated constituencies based on the certified voters roll from the 2021 local government elections. The logic behind this is that demarcation of constituencies would have to be performed well before the general election, and it seemed reasonable to base it on the roll used in the preceding local election.

I viewed it as absolutely necessary that constituencies not cross provincial boundaries, so I first determined the number of seats for each province in proportion to the size of the province’s voters roll. I then determined a quota of voters per constituency for each province. This gave the following results.

| Province | Registered voters | Constituencies | Quota |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Cape | 3,253,307 | 25 | 130,132 |

| Free State | 1,413,158 | 11 | 128,469 |

| Gauteng | 6,195,753 | 47 | 131,825 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 5,447,815 | 41 | 132,874 |

| Limpopo | 2,585,080 | 20 | 129,254 |

| Mpumalanga | 1,903,239 | 14 | 135,946 |

| North West | 1,671,551 | 13 | 128,581 |

| Northern Cape | 622,746 | 5 | 124,549 |

| Western Cape | 3,111,930 | 24 | 129,664 |

I then demarcated each province separately based on these figures. In doing this I allowed each constituency to vary from the provincial quota by no more than 15%.

I used the wards (as used for the 2021 local elections) as the basic building block of the constituencies. I tried to adhere to municipal boundaries as far as possible. I also tried to create reasonably coherent and compact constituencies, and to avoid splitting communities.

I endeavoured not to bias or “gerrymander” the constituencies in favour of any party. I didn’t calculate the voting results for any of the constituencies until I had completed the demarcation. Nonetheless, the demarcation process naturally involves many judgment calls where unintentional bias may have slipped in.

Election results

I used the regional ballot results from the 2024 general election to determine which party would win each of my imagined constituencies. The results came out as follows.

| Party | Vote share | Seats won |

|---|---|---|

| ANC | 39.3% | 117 |

| DA | 21.8% | 48 |

| MK | 14.1% | 30 |

| EFF | 9.8% | 0 |

| IFP | 4.3% | 5 |

| Others | 10.6% | 0 |

The DA wins 21 seats in the Western Cape, 18 seats in Gauteng, and 9 seats in mostly urban areas in the rest of the country.

The IFP wins 5 seats in its heartland of Zululand.

MK wins most of the rest of the seats in KwaZulu-Natal — 28 — leaving only 2 KZN constituencies for the ANC. MK also wins one seat in Mpumalanga, and one in Gauteng. (This last seat in central Johannesburg sees its vote split six ways between MK, ANC, EFF, DA, ActionSA and IFP, and the MK wins it with only a 27% vote share.)

The ANC remains dominant in the rest of the country, taking all seats in the Northern Cape, North West and Limpopo, and the vast majority of seats in the Eastern Cape, Free State and Mpumalanga.

Notably the EFF doesn’t win any seats in this demarcation despite having 9.8% of the vote share. This reflects that the EFF’s support base is not geographically concentrated in any particular area. Combined with the 10.6% of votes given to other parties that don’t win a seat, over 20% of voters are completely unrepresented by constituency MPs.

In 122 seats (61%) the winning party has an absolute majority with over 50% of the votes cast. In the remaining 78 seats the winning party has less than 50% of the vote — the lowest being the aforementioned Johannesburg Central constituency won by MK with 27%. Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal are particularly split, with 64% and 63% respectively of seats in those provinces being won without an absolute majority.

Conclusion

First-past-the-post elections in single-member constituencies produce legislatures that are highly disproportionate to the votes cast. I would not recommend the use of such an electoral system in a country like South Africa with such a variety of parties.

However a mixed-member proportional system, combining directly-elected constituency MPs with list MPs elected to restore proportionality, presents an interesting option for electoral reform. This system is very similar to the one already used to elect metropolitan and local councils. The existence of a local constituency MP might bring more attention to voters’ issues, increasing accountability and the sense of connection between people and Parliament.